An exclusive inside look at London’s legendary Abbey Road, recording studio for Sir Edward Elgar, Glenn Miller, Beyond the Fringe, Pink Floyd, and some group called The Beatles. The music television show, Live From Abbey Road, was taped at the studio and premiered June 2007 on the Sundance Channel.

An exclusive inside look at London’s legendary Abbey Road, recording studio for Sir Edward Elgar, Glenn Miller, Beyond the Fringe, Pink Floyd, and some group called The Beatles. The music television show, Live From Abbey Road, was taped at the studio and premiered June 2007 on the Sundance Channel.

Studio One at London’s legendary Abbey Road Studios reminds one of an enormous airplane hanger. My first thought is the old TV broadcast of the Beatles in this room, singing “All You Need is Love.†In this same space, composer Sir Edward Elgar christened the studio’s opening in 1931 by conducting an orchestral version of “Pomp and Circumstance.â€

Standing in the room is a moment to be savored, imagining what these walls have heard over the years. From Elgar in his tuxedo and moustache, conducting that melody from everybody’s graduation ceremony, to a roomful of hippies in paisley singing about love. To more recently, Kanye West, Iron Maiden, the Red Hot Chili Peppers, and soundtrack recordings for the Star Wars and Harry Potter films.

The world’s most famous recording studio sits tucked away in a nondescript mansion in north London’s posh St. John’s Wood neighborhood. Most of us recognize the name because of the Beatles’ 1969 album Abbey Road, with the iconic cover photo of the band strolling across the striped crosswalk.

Beatles trivia runs deep. Geeks already know that the album was renamed Abbey Road at the last minute (the original title was “Everestâ€), and that the photo shoot took just ten minutes, and that Paul McCartney was supposed to be dead because he was depicted in bare feet, among other “clues.†If a fan makes the pilgrimage to the studio, it’s mandatory to scrawl some Beatles lyrics on the wall in front of the building.

But Beatles mythology is only a small portion of the Abbey Road timeline. It is in fact the industry’s oldest studio, with a long tradition of recording music, comedy and theater. The original name EMI Studios was officially changed to Abbey Road, only after the Beatles’ album became popular.

The facility remains open 365 days a year, 24 hours a day. It never needs to advertise, and is never open to the public. Just a few months ago the studio celebrated 75 years in business. This June the Sundance Channel debuts a new music television show, Live from Abbey Road, taped on the premises.

Because of the upcoming show, Abbey Road managing director Dave Holley and Michael Gleason, producer of the show, have graciously agreed to give me a short tour.

Artists who’ve recorded here have included everyone from Glenn Miller and Noel Coward to Shirley Bassey, Peter Sellers, Beyond the Fringe, the Buzzcocks, the Spice Girls, and Radiohead. Like an old nightclub or theater stage, ghosts hang in the air, invisible to the eye but soaked into the structure itself.

I mention to Holley that I’ve heard U2 was recording here recently. “It’s policy of the studio going back 75 years that we never tell people who’s here,†he answers with a smile. “Because you end up with funny people standing outside trying to get in. We’re doing four films today, not a lot of rock and roll today.â€

There is a rumor, however, that Robert Plant and Jimmy Page from Led Zeppelin are in fact here, in another studio behind the red light. They could be just sipping tea and flipping through magazines, but it doesn’t matter. I’m in the same building with the band I used to play air guitar to in high school.

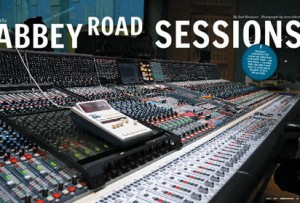

Holley opens a door and shows me Studio One’s futuristic glass-walled control room, bristling with knobs and switches and lights and the staple of every studio, a black leather sofa. This is where engineers mix sound for, say, The Lord of the Rings soundtrack.

Gleason points over to a beat-up Steinway upright piano and gestures for Holley to show it to me.

“Oh yes,†exclaims Holley. “This is the piano that ‘Lady Madonna’ was played on.â€

I run my fingers over the keys, knowing full well that this moment would induce hardcore Beatles fans to wet their pants. The wear and tear from decades of studio recording is evident; the ivories look like an animal had scratched them off.

“It was used on the U2 sessions,†Holley concedes.

Holley breaks down the various elements of the complex. Because the industry makes fewer classical records these days, Studio One has been repurposed for recording and mixing film soundtracks. Studio Two, where Zeppelin is supposedly hiding today, is the most requested room by rock bands, and is where the Beatles made nearly all of their records. Studio Three is slightly smaller, the birthplace of most of Pink Floyd’s albums, and is also occupied at the moment. The Penthouse Studio was built in the mid-late 70s and used by punk/New Wave bands like the Buzzcocks and The Cure. It’s now primarily for digital mixing for films.

Another 17 rooms are used for mixing and mastering records, and digital remastering from analog sources. They’ve recently added a video department, and Holley notes with pride that the very first DVD outside of Japan was made here at Abbey Road.

Beatles folklore describes Abbey Road engineers leaving a marathon recording session and heading to a nearby pub to decompress. Holley says that’s no longer necessary, and walks me down a flight of stairs into the in-house restaurant.

“We’ve pulled the pub to us!†he exclaims. “This is where people tend to decompress. A bit too much for my liking at times! Artists will come and have a drink, orchestra players.â€

“It’s one of my favorite rooms,†he adds. “You see all sorts of people in the same place that you don’t see together.â€

Holley remembers one day at the studio, when the most unlikely group of clients were wandering in and out of the cafeteria. British rock band Starsailor, teenybopper boy band McFly, Roger Waters from Pink Floyd, and operatic tenor Placido Domingo. “That was one of the most bizarre days,†he recalls.

Technology has advanced so much, it’s now common for musicians to never leave their house to create a high-quality recording. Why is a studio still necessary?

“There are different ways you can make things,†explains Holley. “If you want a performance-based record, then you need a space that sounds good, so we’ve got a few of those.

“I actually think, whatever business you’re in, it’s that walking-down-a-corridor moment, where you work with someone,†he emphasizes. “Something comes out of a cup of coffee around a machine. When you work together, two brains are more than twice the value of one brain. I think coming together to work in a community, and coming to a place where there are traditions of working together, with people who are used to doing that, I think you get far more than just working on your own.â€

The tradition of collaboration at Abbey Road extends back to 1931, when EMI transformed a 16-room mansion into the world’s first recording studio. In addition to Sir Edward Elgar, prominent composers and musicians like Yehudi Menuhin, Noel Coward, Artur Schnabel, Fred Astaire, and Fats Waller made recordings in the early years.

During World War II, the studio remained open for BBC radio broadcasts, and hosted wartime entertainers like Gracie Fields and George Formby. In 1944 Glenn Miller made several recordings with Dinah Shore, which were to be his last-ever sessions. His airplane went down in the English channel a few weeks later.

Technical advances were absorbed by Abbey Road throughout the 1940s and 1950s, including the long-playing record, four-track equipment, new magnetic tape, and noise limiters. Pop music and comedy were replacing classical sessions. Comedians like The Goon Show’s Peter Sellers and Spike Milligan were now scheduling studio time alongside pop stars like Eddie Calvert, Ruby Murray and Sir Cliff Richard, whose 1958 single “Move It†is considered England’s first-ever rock and roll record.

It’s worth noting that Richard’s first hit came from Abbey Road, because it was not exactly a rock and roll environment. Because of a strong musicians’ union, normal recording hours were rigid –10 am to 1, lunch break, 2:30 to 5:30, and 7 pm to 10pm. Musicians would enter the studio on time, engineers quickly set up the equipment, and within ten minutes the session had started.

Abbey Road was among the most strict and button-down of all the London studios, with a precise apprenticeship structure and rigid dress code. Balance engineers wore white shirts and neckies, and sat in the control room. The maintenance engineers wore white lab coats, and were the only ones allowed to set up microphones and other equipment. The “brown coats†were janitorial staff.

By the early 1960s, Abbey Road was regularly producing hit records, from Shirley Bassey to Cliff Richard and the Shadows, Manfred Mann, the Hollies, and Cilla Black’s version of “Alfie†with Burt Bacharach. The Beatles made their first record “Love Me Do†at the studio in 1962, and for the next seven years would make nearly all of their records at Abbey Road.

The studio changed forever in 1966, when the Beatles vowed to stop touring live because the screaming fans kept drowning out their instruments onstage. The band planned to make only records, with the idea they would tour an album, rather than tour live.

With no more pressure on creating music to be perfomed, the Beatles were increasingly excited about using the resources of Abbey Road. Technology was pushed to the limits. Band members and producer George Martin scrounged up all sorts of odd instruments, and challenged the Abbey Road staff to cut and splice pieces of music on top of and inside of each other. Often Beatles sessions would use all three studios simultaneously, with engineers dashing back and forth to synch up the primitive four-track recording machines.

According to the memoir of Beatles engineer Geoff Emerick, one of the highlights was a recording session in Studio One for the Sgt. Pepper album song “A Day In the Life.†The basic song was finished, but it needed some strings to fill in a 24-bar portion, one long, loud ascending chord. The Beatles commissioned a 40-piece orchestra to come in, and as an afterthought decided to make the session into a “happening.â€

As orchestra members arrived in their evening tuxedos, they were handed a clown wig, or rubber nose, or gorilla paws. Wine was flowing, as well as a few other substances. Celebrities like Donovan and the Rolling Stones were hanging about. Emerick recalled studio managers Bob Beckett and E.H. Fowler, two proper men in their sixties, standing at the rear of the room in pinstriped suits and starched white shirts, watching classically trained musicians attempt to play their parts, surrounded by balloons and drunken hippies, and sadly shaking their heads. Emerick thought to himself, “This really is a passing of the torch.â€

Another milestone for Abbey Road was the 1973 Pink Floyd concept album Dark Side of the Moon. At the time, the band was at a crossroads. They were moderately successful, but their singular brand of hippie experimental psychedelia was old news. A new album needed to change course, or they were finished.

Taking a cue from the Beatles, Pink Floyd pushed the studio’s boundaries to the limit, raiding the EMI sound effects library and splicing tape loops around the control room. They programmed keyboard sequences, and experimented with ambient sounds of chiming clocks, clanging coins and cash registers. No rock record had ever sounded like this before.

The album took seven months to complete. In the final days, chief songwriter Roger Waters decided to layer some human speaking voices in and out of the record, to give it some texture. He gathered a handful of people hanging around the building to ask them questions about topics like death and insanity. Among the group were Pink Floyd roadies, Abbey Road staff members, and Paul McCartney, who happened to be recording with his band Wings.

An older “brown coat†Irish gentleman named Gerry O’Driscoll, Abbey Road doorman at the time, proved one of the session’s stars. His voice ended up immortalized on the record: “I’ve always been mad. I know I’ve been mad like most of us have. Very hard to explain why you were mad, even if you’re not mad.â€

Since its release, Dark Side has been on the charts for over 28 years, spending an incredible 741 consecutive weeks on the Billboard 200, a feat unequaled by any record in history. It’s estimated that one in every 14 Americans under the age of 50 has owned a copy of this album.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Abbey Road branched out into recording of film scores, while keeping a hand in the emerging Britpop scene. Bands such as Radiohead, Gomez, Blur, and Manic Street Preachers all used the studio. The Spice Girls’ sessions in Studio Three attracted fans and media from all over the world, camping outside the entrance. The Beatles legacy came full circle in late 2006, when Sir George Martin and his son Giles raided the Abbey Road archives to create the revolutionary mashup album Love.

“Seventy five years ago, you literally came to the one microphone, and you stood exactly where you were told,†says Dave Holley. “The artist was very much secondary to the technical engineers. You performed when we told you to. And now, it’s all twisted the other way, and anybody can make anything.â€

The very nature of the music industry has changed the way Abbey Record does business. More people are creating music, and more people are consuming it in a variety of ways, from iPods to ringtones and interactive websites.

“The process is speeding up,†Holley continues. “People are like magpies, they take what they need — digital, analog, locations, working at home, using different people for different tracks, and then using different people to mix different tracks. I think the palatte is wider. What we’re trying to be is to offer a place where people can come come together to try things.â€

————————————-

Outside Dave Holley’s office window, tourists are taking photos of each other on the famous crosswalk. Holley and Michael Gleason sip cups of tea as they explain the origins of their new TV show Live From Abbey Road. With the cancellation of the U.K.’s long-running Top of the Pops, and MTV rarely airing any music videos, there’s not much actual music television anymore. This show is designed to fill the void.

Other than the Beatles’ “All You Need is Love†broadcast, and a few other programs over the years, Abbey Road has rarely opened its doors to a television or film crew. This upcoming series will be revolutionary for a few reasons.

Each segment features two to three artists, performing live in Abbey Road. There is no live audience, and no host or presenter. Focus is solely on the music. Performers range from Dr. John and Wynton Marsalis, to Norah Jones, Snow Patrol, Gnarls Barkley, Muse, The Kooks, and Irish singer-songwriter Damien Rice.

“You get an actual raw performance,†says show producer Gleason, a Texas-born investor and former director of MGM Studios. “You feel like they’re performing for you. The building is the host of the show. Dave Matthews came in, he loved being in that room. Jay Kay from Jamiroquai, he just went on and on about how he loved the vibe of the room. Because it’s a cool place. There are other recording studios around, but the magic is here. It’s just got that special sense.â€

“In the studio you see the masks slip a little bit,†adds Holley. “You get to see them relaxed, you get to see them playing rather than performing. You get to see a little closer. Simplicity really works. Because you’ve got time to really let it breathe and enjoy it.â€

The show’s segments are beautifully shot in high-definition video with several cameras, and some pieces are reminiscent of photo essays, with closeups on a drum highhat, or fingers on a keyboard. It’s almost as if the show is set up to prove a point, that songs don’t have to be created to climb the charts, or sell sneakers. Music should be appreciated for what it is. This is for the purists, an MTV Unplugged that’s grown up.

“Each of the artists performs in different ways,†says Holley. “It’s lit differently, shot differently. Massive Attack looks iconic, almost like something from the Newport Jazz Festival in the 60s. Then you’ve got The Killers, which is much more intimate. You’ve got Corinne Bailey Rae, she’s like a 40s movie star. It’s so interesting. It doesn’t feel like the same show each month.â€

The first season of Live from Abbey Road filmed 38 artists in 12 shows, and is already licensed to 89 countries. Channel 4 in the UK has already aired the show, and the Sundance Channel begins running the series this summer in the U.S. If reaction is as expected, another season will begin shooting this October.

There’s an unmistakable feeling of family in Abbey Road. Most of the staff from the old days continue to drop by and say hello. Even engineers from the once-rival Olympic Studios, who worked on records by Led Zeppelin and the Rolling Stones, will keep in touch.

A 75th anniversary party last November attracted pop and rock music’s best recording engineers from throughout the decades. Did anybody put on the old lab coats?

“No, I was expecting one or two, but to be honest I don’t think they would have fitted many of them,†says Holley. “There’s one or two girths that have obviously grown since then!â€

# # #

(A version of this story first appeared in American Way magazine)