It’s 7 a.m. in Prague and I’m walking around the perimeter of Strahov Stadium, a crumbling sports arena left over from the Communist regime. During the spring 1968 invasion, citizens removed all street signs and numbers to confuse Soviet troops. Apparently the tactic is still successful because I have no idea where I am. Somewhere nearby is a training center for Prague’s chapter of the Czech Sumo Union. I’m here for the morning sumo practice.

It’s 7 a.m. in Prague and I’m walking around the perimeter of Strahov Stadium, a crumbling sports arena left over from the Communist regime. During the spring 1968 invasion, citizens removed all street signs and numbers to confuse Soviet troops. Apparently the tactic is still successful because I have no idea where I am. Somewhere nearby is a training center for Prague’s chapter of the Czech Sumo Union. I’m here for the morning sumo practice.

Mention the Czech Republic and things come to mind like hockey, pilsner beer, American expatriates, or maybe a Sports Illustrated swimsuit girl. But sumo? Isn’t that for huge Japanese guys? One of the E.U.’s biggest secrets, it turns out, is that outside of Japan, the Czech Republic is sumo’s most popular country. There are only 50 wrestlers in the United States, but the Czechs claim over 500, more than any of the other 25 sumo-friendly European nations.

Today I’m to meet Jaroslav Poriz, president and founder of the Czech Sumo Union. He’s the country’s most famous wrestler, ranked fifth in the world and fifth in Europe. He also organizes the tournaments, recruits new wrestlers, sets up sumo clubs statewide, and coaches a daily practice session. Poriz is the man. That is, if I can find him.

Two men in street clothes stand in front of a grubby steel door, talking in Czech. One is huge, easily six feet, five inches, the other- almost comically small in comparison, around five feet, four inches. I inquire about the sumo club, and they reply in broken English that yes, this is the right location. Out of Czech’s booming sumo explosion, exactly two have shown up for practice.

A gleaming black car screeches to a stop, and Poriz hops out, wearing a long leather coat, his head shaved except for a thick tuft of hair sprouting out the top. He introduces- me to the others. The big wrestler is Jiri Kolbl,- a scientist and former judo champion. The smaller guy is Jakub Sara, who placed at the world championships two years ago.

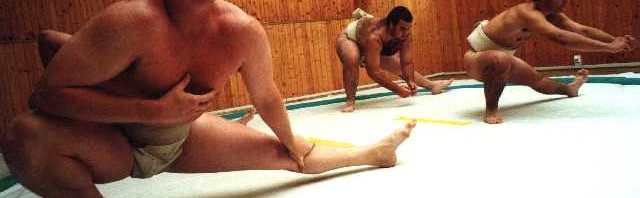

The Sumo Strahov clubroom is lined with wood paneling. A sumo ring, or dohyo, dominates the dirt floor, a banner reads “Czech Sumo Union 1st European Sumo Training Center.†Three straw brooms lean against a wall. Poriz directs me to a chair — actually, the only chair. The guys disappear into a locker room and emerge wearing nothing but the diaper-like mawashi around their waists.

My knowledge of sumo runs as deep as the silly sumo scenes in the Austin Powers and Charlie’s Angels films. It does seem that the sport won’t be saturated with sponsorship anytime soon, because there’s no room on the uniforms for the Nike logos. The wrestlers do some stretches and exercises, shouting phrases in Japanese that sound like, “Soo-ha!†and “Hight!â€

The men take turns in practice bouts. Sara loses every time, because he weighs half as much as the others, but he’s feisty and doesn’t back down. Occasionally Poriz shouts instructions in Czech, something about keeping the elbows tucked in. The best matches are between Poriz and Kolbl, two enormous man-bulls slamming into each other, more than 600 total pounds of struggling and huffing flesh, until one is shoved out of the ring. All three then squat around the dohyo perimeter with eyes closed, and do a quick chant. Practice is over. Sara waters down the ring with a hose, the others grab brooms and whisk the dirt, like suburban dads casually cleaning the driveway. Poriz comes out of the showers and says to me, “Come on, let’s go get some breakfast.â€

We step inside a nearby school cafeteria and walk up to the register. Poriz looks at the menu with a frown, and then turns to me and asks, “You want a beer?†I glance at a clock. It’s 8:30 in the morning. In Prague, there’s nothing unusual about having beer for breakfast with a 31-year-old, six-foot, nine-inch sumo wrestler who works as associate editor of a Czech business daily -newspaper.

Sumo in Japan traces back to 700 A.D., but Czech sumo dates back only to 1997, explains Poriz, with wrestlers practicing in city parks until the Strahov training center was built. Since then, the Czechs have opened 10 clubs all over the country, from Prague to Moravia and northern Bohemia. Czech wrestlers place each year in amateur world tournaments. In 1998, Poriz took a Czech team to Japan and practiced at a professional- sumo stable for a month, the first foreign team in 5,000 years to be allowed such privilege. One of his students currently- works in Japan as an apprentice, and recently has turned professional. A Czech tournament center and hotel in Jilemnice, a small mountain town near Poland, is the only one of its kind in Europe.

Despite all these accomplishments, the idea of a Czech sumo juggernaut has somehow escaped most of the Czech population. Before meeting up with Poriz, I spent a week in Prague and asked locals if they had heard of this sport sweeping their nation. Some laughed out loud at the idea. Others were astonished something would even exist. “It sounds interesting,†one woman told me, “but it’s not something I’d be interested in.â€

Poriz returns to our breakfast table with two fresh beers, and I venture a theory that Czechs gravitate to sumo because a majority- of men might be overweight? No, he says, most Czechs are small in size. Are the Czechs naturally aggressive? Poriz roars with laughter. “Czech people are timid.- The Czech character is like, we always yield. We’re unlike the Poles. The Poles always fought every invasion. The Czechs never fought anything. They gave up.â€

The true reason behind the popularity of Czech sumo is Poriz. He works hard to recruit new wrestlers, attending sports events, watching for kids who look tough. He works the phones, reminding wrestlers of practices and tournaments. And he finances wrestlers’ expenses to tournaments out of his own pocket.

Most European countries that have sumo aren’t really enthusiastic, Poriz says, until it becomes an Olympic sport, and then they will benefit from government funding. The Czechs do sumo at the amateur level, without any government sponsorship, only because of Poriz’s enthusiasm.

Poriz first saw sumo in the 1980s, while growing up with his family in the Czech Republic. His father returned from a business trip to Japan and brought back a videotape of sumo wrestling.

“To me it was sort of like the cartoons — out of this world. These huge guys hitting each other, like monsters, or dragons. But I didn’t think of doing sumo. It was entertaining.â€

Poriz later attended John Carroll University in Cleveland, Ohio, and befriended a Japanese exchange student whose uncle was a former sumo wrestler. His friend mentioned he should try sumo, so Poriz started checking out sumo magazines and videos.

“I really started seeing sumo, and thinking, Hey, this is interesting. It’s not just like the fat guy wins. It’s really intense,†he says. After school, he returned to the Czech Republic, discovered there was European amateur sumo, and started the Czech Sumo Union in 1997. He found a Japanese ex-sumo wrestler to coach a team, and they went to the European World Championships. He placed fifth.

“It was unbelievable,†he remembers. “I had two months of practice! We had nothing, we had no club, we just practiced outside on the lawn Friday afternoons after work.â€

Today, Poriz counts sumo champions like Konishiki among his friends. He’s traveled to Japan over 30 times, and is so well-liked the Japanese have given him a sumo fighting name: ShiroiKuma, aka “White Bear.†One of his biggest achievements was beating Manny Yarbrough, the former world champion from New Jersey.

A regular guest on American late-night talk shows, Yarbrough owns the distinction of heaviest sumo wrestler in history. His weight drifts from 800 to 900 pounds, and at his peak in the late ‘90s he was unbelievably strong and agile, routinely beating the Japanese at their own sport. Poriz had the dumb luck of drawing Yarbrough’s name at almost every world championship, and losing to him. But he learned something profound about sumo from the experience.

“I realized that sumo is like life,†he says. “If you should be a warrior, the winning is understood. Many times you fix yourself on the object of winning, but you forget that what matters is the path that you take there. The practice, the many times you’ve been hurt. You have to overcome those little difficulties, not the big ones. And that makes you something better.â€

Sumo appears different to the Western world, he says, because sports are valued on winning, rather than the process. Sumo has changed his perspective on every-thing: life, work, career advancement. “Most people toil all day, stress about their boss. That’s where sumo comes in. If you do something, try to do it as good as you can. If you’re fixated on someone’s approval, you’ll grow into what you do. If you overcome yourself every day, you’ll become the man everyone’s afraid to face.â€

Jilemnice sits in the lower Giant Mountains of Northern Bohemia, 30 kilometers from the Polish border. The town has existed since 1352, but only in the last year has it boasted a nine-meter-high statue of a sumo wrestler. Poriz and his father opened Hotel Sumo in 2000, adding oversize Japanese-style furniture, a wine cellar, and a bathtub large enough to hold my rental car. The hotel hosts sumo tournaments for all of Europe, welcoming wrestlers from 16 countries, and functions as a regular hotel between events.

Poriz’ father, also named Jaroslav, walks me through the building and pulls back a wall of the restaurant to reveal an authentic dirt-floor dohyo. Sumo practice can be watched without having to leave the table. Wrestlers come here from all over the world to train, mostly from Japan, and stay for approximately 10 days, helping European wrestlers sharpen their skills.

On my flight from London, a Czech named Vladimir had told me the outstanding characteristic of Czech people is the “grumpiness.†Poriz senior is anything but grumpy, laughing constantly and cracking jokes, many of which are intended solely to embarrass his son. He gestures to clippings framed on the wall, from a world championship tournament when he was the coach of the Czech sumo team. A wrestler dropped out at the last minute, so at age 47, Poriz senior participated in his place. He won his match, the first and only of his career, and pushed the Czech team into fifth place.â€It was a 30-second match,†he says, “and then I retired. I left all my powers in dohyo!â€

The three of us sit outside at tables, and a sumo chef serves us sumo steaks, essentially a slab of beef spilling over both sides of the plate, accompanied by tiny dollops of mustard and paprika. And more beer, of course. The sumo appetite is startling to observe in person. I watch Poriz and his father take bites three times the size of mine. When they’ve cleaned their plates, I’m not even half done. “More beer?†says Poriz senior. I answer, “No thanks, I’m fine.†He sets another in front of me. “You will be finer.â€

We walk through the streets of Jilemnice and end up at an old abandoned factory building. The Porizs have just bought this structure, and sometime next year construction will begin on what they plan to open as a fabulous 1,000-seat sumo competition arena. There are only two such sumo facilities in the world; this will be the third. It’s an astonishing effort to be sure, the father and son teaming up to develop their country as the capital of European sumo.

“In Japan there are only two sumo arenas,†says Poriz. “This is going to be the only one outside of Japan.â€